Deployment of renewable electricity will reduce reliance on gas in the power system and cut emissions. While the failure to secure any additional offshore wind capacity in last year’s auctions was a setback, the Contracts for Difference model remains the best way for the UK to bring forward renewable capacity.

Government should continue to focus on delivering renewable deployment at pace, as well as bringing forward firmer plans and finalised business models to deliver flexible generation for when the sun does not shine and the wind does not blow. Investment in transmission and distribution networks must also keep pace with demand. The plans to accelerate transmission infrastructure and connections to the network are welcome steps forward. Government should also continue progress on improving governance, including completing the setup of the National Energy System Operator and its critical system planning role.

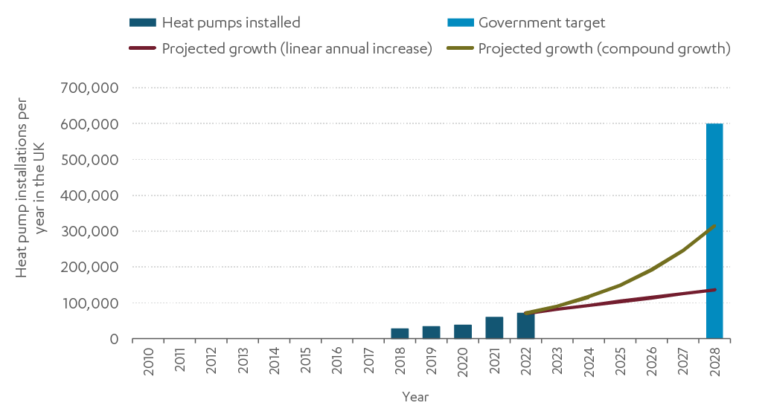

Decarbonising buildings is the single biggest challenge on the path to net zero, requiring almost all households to engage in the transition. Government must step up the level of ambition on energy efficiency and heat. Current plans are insufficient to meet the target of 600,000 heat pump installations per year by 2028.

The Commission’s view is that electrification is the only viable option for decarbonising buildings at scale, and the solution for most homes will be heat pumps. They are highly efficient, available now and are being deployed at scale in other European countries. The second National Infrastructure Assessment set out how policy should focus on building the market and supporting consumers to make the transition.

There needs to be a comprehensive, long term and funded plan to reduce energy demand and make the transition to electrified heating. While the increase to the subsidy for heat pumps is positive, other important elements of the transition are going backwards. Continuing uncertainty over the role of hydrogen in home heating is also contributing to slow progress in this area.

New networks to transport carbon and hydrogen are vital to support decarbonisation across the economy. The government has published a hydrogen transport and storage networks pathway, agreeing in principle with the strategic case for building a core network made by the Commission. The government has also published a vision for the evolution of the carbon capture and storage market. Government should make further progress in coordinating and supporting the delivery of this infrastructure, as well as increasing the pace of delivery of the business models required to support these new sectors.

State of the sector

The energy sector covered by the Commission largely consists of two key networks: electricity and natural gas.

The electricity system includes infrastructure that generates electricity, such as wind turbines, solar panels, nuclear power stations and gas fired power stations. Because electricity supply needs to match demand at all times of the day and year, flexibility is required. This is provided by generation through flexible sources, storing electricity, or reducing demand through demand side response. The electricity transmission and distribution networks supply the vast majority of homes and businesses.

In order to deliver a low cost, low carbon energy system, gas generation will need to be replaced primarily with wind and solar power, supported by low carbon flexibility. This will come in the form of technologies such as batteries, demand side response and flexible generation through hydrogen and gas with carbon capture and storage.

Additional capacity in the electricity transmission and distribution networks will be required to meet the higher levels of electricity demand from electrifying heat, transport and industry. More than 17 new nationally significant electricity transmission projects will be required in England and Wales by 2030 to support electrification, a more than fourfold increase on historic rates. Lack of electricity network capacity is already leading to increased costs for consumers. By 2030, network constraint costs caused by insufficient capacity are estimated to rise to between £1.4 billion and £3 billion per year, unless the capacity of the transmission network is expanded.

The natural gas network is connected to around 85 per cent of homes. Natural gas is used to heat most homes and businesses, as well as to generate electricity. Other sources of energy, such as oil and biomass, are also used to heat buildings, but in smaller quantities. Some homes are also heated with electricity.

Moving away from gas heating will be essential for reducing carbon emissions in homes, as well as improving air quality and permanently reducing heating costs for households. Seven million buildings need to switch from fossil fuel heating systems to heat pumps or heat networks by 2035.

The sector also includes new infrastructure to support hydrogen and carbon capture and storage. This infrastructure will be essential to decarbonising the electricity system, as well as being used to decarbonise some industry where electrification is not feasible. Carbon capture and storage will also be key to facilitating engineered greenhouse gas removals. Enabling these uses will require infrastructure to produce, transport and store hydrogen, as well as to capture, transport and store carbon.

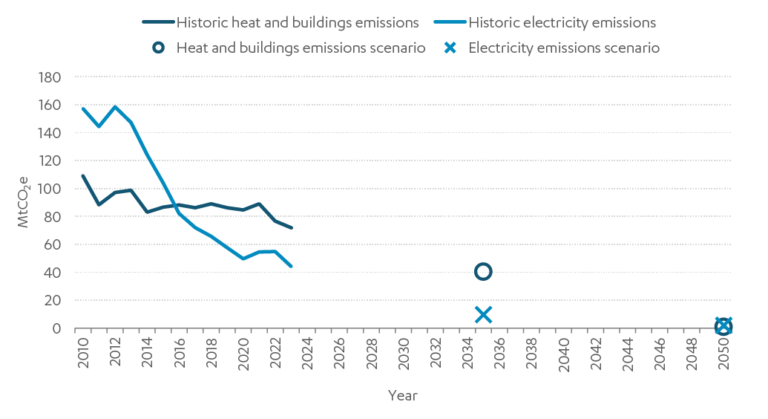

Greenhouse gas emissions from the energy sector have reduced (figure 2.1), driven primarily by the successful move away from using coal to generate electricity. However, emissions remain too high, driven by the continued use of gas for electricity generation and heating.

Emissions from electricity will need to fall to near zero by 2035 to meet the sixth carbon budget. Emissions from heat need to reduce by around 50 per cent by 2035 from 2019 levels, and to near zero by 2050. In addition to reducing carbon emissions, moving away from gas for electricity generation and heating should lead to lower costs for households and businesses, and reduced vulnerability to energy shocks.

In 2023, emissions from heat and buildings and from electricity generation were roughly 20 per cent lower than in 2021. This is most likely driven by high fuel costs. In particular, the reduction in emissions from heating is most likely driven by lower use of heating in buildings, rather than a transition to cleaner fuels.

Figure 2.1: Emissions reductions have been driven by electricity in recent years, but progress has stalled

Actual and potential emissions in the government’s net zero delivery pathways, United Kingdom

Source: Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (2023), Final UK greenhouse gas emissions; Climate Change Committee (2020), Sixth Carbon Budget

Note: Energy sector emissions include Energy from Waste

The cost of energy to households and businesses remains elevated, but has fallen significantly in the last year, driven by reductions in the price of gas, which affects the cost of electricity and heat.

In the absence of government intervention, energy costs for a typical household would have peaked at £4,279 a year between January and March 2023. Direct subsidy from government reduced this to £2,500 a year. This has fallen to £1,690 a year between April and June 2024.

The Commission has set out a more detailed overview of the energy sector in the Second National Infrastructure Assessment: Baseline Report Annex B: Energy and the Commission’s historic data on sector performance is available online.

Progress against the Commission’s recommendations

Electricity system

Overview of key government policy

The government has committed to decarbonise the power system by 2035, subject to security of supply. To support the delivery of a decarbonised power system, the government has:

- set technology specific targets for low carbon generation, including 50GW of onshore wind by 2030

- agreed to deliver annual contracts for difference auctions and has reopened these auctions to onshore wind and solar projects

- made changes to the National Planning Policy Framework to loosen the effective ban on onshore wind in England.

The government is conducting its Review of Electricity Market Arrangements, and has issued a second consultation narrowing the range of potential options to reform electricity market design. As part of this second consultation, the government said that a limited amount of new unabated gas capacity was likely to be needed during the transition to a decarbonised system, in order to ensure security of supply.

In 2021, the government and Ofgem published an updated Smart Systems and Flexibility Plan, which estimated that a tripling of low carbon flexibility capacity would be needed by 2030. The plan set out several actions to reduce barriers to deployment. As part of this work, the government has consulted on a policy framework to de-risk investment in long duration electricity storage.

The government and Ofgem have also set out a number of policies to improve governance of the energy system. The 2023 Energy Act legislated to give Ofgem a statutory net zero duty and also legislated for the set up of the National Energy System Operator. This is expected to be established in summer 2024 and will take over the operation of the electricity network, as well as taking on a larger role in planning the energy system, including producing a strategic spatial energy plan. Ofgem also announced in November 2023 that they would proceed with the creation of Regional Energy System Planners, to be delivered by the National Energy System Operator.

In November 2023, government published a Transmission Acceleration Action Plan. This set out actions to reduce the time taken to build network infrastructure, based on the recommendations in the Electricity Networks Commissioner’s report. Government and Ofgem also jointly published a Connections Action Plan, intended to reduce the time taken for customers to connect to the electricity network.

The government has set an ambition for up to 24GW of new nuclear power to be delivered by 2050, and reiterated this ambition in the nuclear roadmap published in January 2024. The government is supporting investment in the new nuclear plant at Sizewell, and has made £2.5 billion in funding available. The project is seeking to reach a final investment decision before the end of this Parliament. Government is also running a competition to select preferred designs for Small Modular Reactors, with the hope of deploying the first reactors by the mid-2030s.

Change in infrastructure over the past year

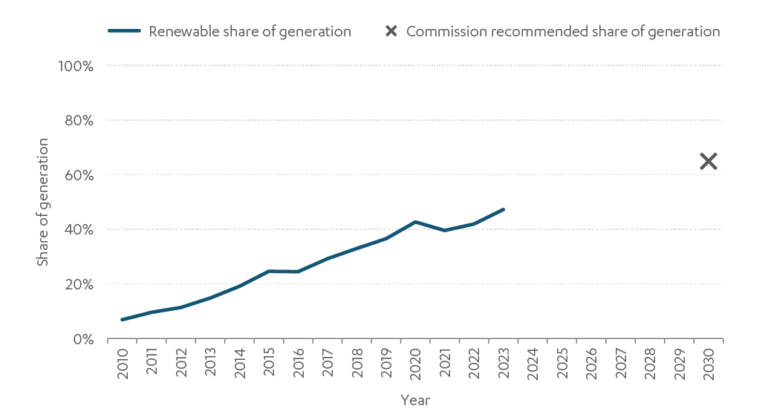

The share of electricity generated by renewables was 47 per cent in 2023. This is the highest share to date, driven by a reduction in fossil fuel generation, particularly gas.

The volume of electricity generated by renewables in 2023 was 135TWh — the highest volume to date, equal to 2022. The government remains broadly on track to deliver 65 per cent of generation from renewables by 2030.

Figure 2.2 Renewable deployment is broadly on track to deliver the Commission’s recommendation

Historic share of generation and Commission target of 65 per cent by 2030, United Kingdom

Source: Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (2023), Energy trends: UK renewables

The government’s contracts for difference scheme continues to procure new renewable capacity at low prices. The fifth round of auctions in 2023 awarded contracts to 3.7GW of low carbon generation, including 1.5GW of onshore wind, primarily in Scotland, and 1.9GW of solar.

However, the auctions failed to bring forward any new offshore wind capacity. The government is looking to rectify this by setting a higher maximum price for next year’s auctions. In order for the government to hit its target of 50GW of offshore wind by 2030, this will require markedly increased ambition in future auction rounds. Energy UK has estimated that at least 10GW of offshore wind will need to be procured in each of the next two auction rounds for this target to be hit.

No onshore wind projects in England were successful in this year’s auctions. Onshore wind capacity in England increased by only 7MW in the year to December 2023. According to government’s Renewable Energy Planning Database, eight onshore wind projects submitted planning applications to build projects in England during 2023. Six of these were applications to replace existing turbines. The remaining projects have applied to build two turbines with a total capacity of 2.5MW. One of these applications has been denied permission, and the other is awaiting a decision.

Assessment of progress

Government is facilitating a rapid deployment of renewable electricity generation and has ambitious commitments and policy in place to support delivery over the next decade. Government is also taking action to bring forward flexible generation, including through the Review of Electricity Market Arrangements. It is critical that this is completed quickly and accompanied by appropriate funding so that technologies can be deployed at pace.

A small role for unabated gas in 2035 is consistent with the pathway set out in the second National Infrastructure Assessment. Where unabated gas capacity is needed to support security of supply, government should put measures in place to ensure that this capacity is only generating when truly necessary and has a clear pathway to decarbonisation. Government should also take action to ensure that unabated gas use is not locked in for longer than it is needed on the system through capacity market contracts that extend beyond 2040.

Ambitious deployment of hydrogen generation and gas with carbon capture and storage will also be essential in minimising the role of unabated gas. Government should move faster to ensure the delivery of multiple large scale projects by 2030, in order to meet the 30TWh of persistent flexible generation that is needed by 2035, as set out in the second Assessment. In particular, greater urgency is required to bring forward policy decisions on support for these technologies and firm funding envelopes.

A coherent plan to bring together government’s policies to decarbonise the power sector would provide additional certainty and clarity on the pathways for individual technologies. This should include an intention to bring forward at least 8TWh of hydrogen storage, as recommended in the second National Infrastructure Assessment. Government should also take action to develop a strategic reserve of energy in the longer term, as recommended by the Commission and the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee.

There has been progress on removing barriers to deployment. The Connections Action Plan and the Transmission Acceleration Action Plan, if fully and rapidly implemented, should help to ensure that projects are not slowed down by insufficient transmission capacity or an ineffective queueing system. However, the changes to planning policy in England to enable onshore wind are not sufficient to enable delivery. This is impeding deployment of one of the cheapest renewable technologies, leading to higher bills for consumers.

- Taking long term decisions and demonstrating staying power: Met. The government has set a clear goal of a fully decarbonised electricity system by 2035 and is taking action to ensure this can be achieved, including speeding up deployment of transmission infrastructure to support increased electricity demand. The government has also recognised the critical role of flexibility in delivering a decarbonised system, and has set out assessments of how much flexible capacity will be needed that are similar to those in the second National Infrastructure Assessment.

- Policy goals must be matched by effective policies to achieve them: Partly met. Policy mechanisms are in place to fund renewable technologies, and other policies are in train to ensure that flexible technologies can come forward. These need to be brought forward more quickly to ensure that delivery can match the levels of ambition on decarbonisation. More attention also needs to be paid to an overarching plan for meeting government’s commitment to decarbonise the electricity sector by 2035. This should include measures to ensure that unabated gas generation is not locked in for the long term, including not issuing capacity market contracts for unabated gas that would extend beyond planned dates for decarbonisation.

- Firm funding commitments: Partly met. The contracts for difference scheme has brought forward significant renewable generation. While this year’s auctions failed to bring forward any new offshore wind capacity, the mechanism remains fit forThe decision to increase the administrative strike price for the 2024 auction round should increase the likelihood of bids from offshore wind developers, but a step change in deployment will be required if the government is to hit their target for 50GW of offshore wind by 2030. Additional funding will be needed to deploy flexibility solutions to ensure security of supply. In most cases, the business models are being developed, but it is not yet clear how much money will be made available. Government must ensure these technologies can be deployed at the scale required.

- Removing barriers to delivery on the ground: Partly met. The government is on track to reach the level of renewable deployment recommended by the Commission. There has also been progress on reform to the planning system and ensuring that transmission network capacity can be delivered to support the deployment of renewables. The connections action plan should help to reduce the time taken to connect to the grid, though initial indications are that the queue to connect to the network is still growing at pace and more action will be needed. Action in other areas has been insufficient. In particular, not enough has been done to enable onshore wind in England, where changes to the planning system to enable deployment are not sufficient to unlock delivery. Onshore wind should be brought back into the Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project system, as well as being treated in the same way as other technologies in the local planning system.

Heat and energy efficiency

Overview of key government policy

The government has set a target of 600,000 heat pump installations a year by 2028, and has set out some policies to deliver this.

The government plans to introduce the Future Homes Standard in 2025, and consulted in December 2023 on how this could be implemented. This will require new build homes to be installed with low carbon heating from 2025.

The Boiler Upgrade Scheme offers grants of up to £7,500 for households and small non-domestic properties in England and Wales that install air source heat pumps. The maximum grant was increased from £5,000 in October 2023. As part of the previously announced £6 billion of funding for energy efficiency and heat between 2025 and 2028, an additional £1.5 billion of funding has been allocated, increasing the annual funding to £500 million.

Government is also taking some steps to make installing a heat pump easier, including consulting on new permitted development rights to reduce barriers to installation.

Some policies intended to deliver low carbon heating have been rolled back. In September 2023, the government announced that new fossil fuel heating installations in off gas grid homes would be banned from 2035 instead of in 2026. The government also announced that around a fifth of homes would be exempt from switching to low carbon heating, but have not set out how this exemption would work.

The government has delayed the implementation of the Clean Heat Market Mechanism, an obligation on manufacturers of fossil fuel heating appliances to also sell a specified number of heat pumps.

The government intends to make a decision on the role of hydrogen in heat by 2026. There is not yet an appraisal framework for how this decision will be made, and government will not have the previously expected evidence from large-scale trials to support this decision. Two hydrogen village trials were cancelled in 2023 in Whitby and Redcar., The smaller H100 hydrogen trial in Fife has been delayed and is now due to begin supplying homes in summer 2025, though this uses a newly built network rather than converting existing gas infrastructure.

The government has announced an ambition to reduce energy use in buildings and industry by 15 per cent by 2030, compared to 2021 levels.

To deliver energy efficiency improvements, the government has several existing schemes for social housing, public sector buildings, and low income households that are off the gas grid. There are also two energy efficiency schemes delivered through energy companies, including the Great British Insulation Scheme (previously known as ECO+) which was launched in 2023 and delivers improvements to a wider range of households than are eligible for other schemes.

In September 2023, the government announced that they would no longer pursue higher minimum energy efficiency standards for landlords. These measures were originally consulted on in 2020.

Change in infrastructure over the past year

Heat pump installations increased to 71,000 in 2022, a 19 per cent increase on the previous year. However, even assuming a 30 per cent increase in installations per year – roughly the average over the last five years – the target for 600,000 heat pump installations per year will not be met (figure 2.3).

There is evidence that the government’s recent increase to the value of the Boiler Upgrade Scheme grant has increased take up. There were 7,290 applications for the scheme between October and December 2023, a 75 per cent increase over the previous three months.

Figure 2.3: Heat pump installations are growing, but the government’s target is unlikely to be met

Number of heat pump installations in buildings, 2018 to 2022, United Kingdom

Source: Climate Change Committee (2023), Mitigation Monitoring Framework, Department for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy (2020), The Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution

Energy demand from domestic buildings fell significantly in 2022. This is most likely to be driven by high energy costs rather than improved energy efficiency. The average energy efficiency rating of homes has not significantly improved since 2020, and the proportion of homes with key insulation measures, such as loft and wall insulation, has also remained flat.

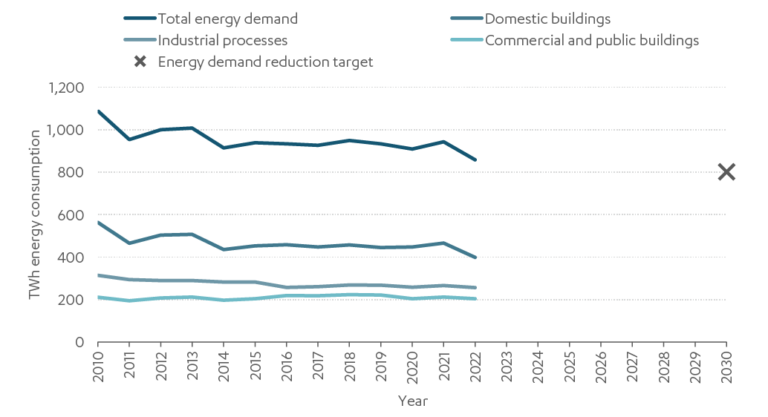

Figure 2.4: Energy demand fell significantly in 2022, driven by domestic buildings

Total energy consumption from domestic and commercial households and industrial processes 2010 to 2022 and government 2030 target, United Kingdom

Source: Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (2023), Digest of UK Energy Statistics, Table 1.1, 1.1.5

Assessment of progress

Government is not on track to deliver its commitments on heat.

Government’s current policies are not sufficient to deliver its stated targets for 2028, nor to switch seven million buildings from fossil fuels to electrified heating by 2035, as is required to meet the sixth carbon budget.

The increase in the maximum subsidy for heat pumps in the Boiler Upgrade Scheme is welcome and in line with the recommendation in the second Assessment. But funding alone cannot overcome the barriers to deploying clean heat, and the promised amounts are not sufficient to deliver the required change. Other barriers to electrifying heat include low public awareness, a nascent supply chain and the continued failure of government to make progress on reducing the running costs of a heat pump relative to a gas boiler. Recent decisions to delay or reverse regulatory policy will also slow the transition and make it harder for government to meet its targets. These policy changes add uncertainty, discourage households from switching to low carbon heat, and discourage businesses from investing in the sector. These decisions will also necessitate speeding up an already ambitious deployment trajectory in later years.

Waiting until 2026 to make a decision on the role of hydrogen in heat compounds this uncertainty. As the Commission set out in the Assessment, there is no public policy case for providing support and government should therefore rule out providing public support for hydrogen heating.

These challenges must be urgently resolved to meet the sixth carbon budget. Government has said that they are confident they can meet their target for deployment of 600,000 heat pumps a year by 2028 despite recent changes in policy. Government must set out how this will be possible, as deployment is clearly off track.

While energy demand from buildings and industry has decreased in the last year, primarily driven by high energy costs, there is no concrete plan for sustained demand reductions through increased energy efficiency. Government is relying heavily on centrally managed funding pots which are not big enough or sufficiently long term to drive meaningful change. Government should ensure that funding streams for energy efficiency are sufficiently long term to allow the industry to plan ahead, and devolved to local authorities for delivery rather than being centrally managed.

There are particular weaknesses in policy to support the owner occupied and private rented sectors. Cancelling higher energy efficiency standards in the private rented sector has created material uncertainty for landlords and tenants. There is no effective policy to replace these regulations and tenants will pay higher energy bills as a result.

Government must begin planning to decommission or repurpose the gas grid. This should include ending new connections to the gas grid from 2025 and ruling out government support for hydrogen for heat. Failing to plan for this transition risks placing higher costs on vulnerable households. As households and businesses switch to electrified heat, the costs of running the gas network will be shared between a smaller number of remaining gas users. An unplanned transition may mean that those last remaining users are households who would find it most difficult to switch, and are least able to bear the additional costs of running the network.

- Taking long term decisions and demonstrating staying power: Not met.

Government has set out some actions to drive heat pump deployment and energy efficiency, but there is limited detail beyond 2028. Recent announcements have added to confusion about the long term direction of policy. These include the announcement that 20 per cent of homes would be exempted from transitioning to low carbon heat in 2035 and the decision to delay the implementation of the clean heat market mechanism just weeks before implementation. Waiting until 2026 to make a decision on the role of hydrogen in heating is also creating long term uncertainty for the sector. - Policy goals must be matched by effective policies to achieve them: Not met. Policies to deliver low carbon heating such as the increased Boiler Upgrade Scheme grant should deliver progress in the short term. But these policies are not sufficient for the task at hand and, as the National Audit Office has observed, the overall pathway for decarbonising heat is not clear. Current policy for decarbonising heat relies heavily on centrally controlled funding pots, and is not supported by effective regulatory, financial or enabling policy. A concrete plan is needed for improving energy efficiency in homes, particularly in driving action for owner occupiers and the private rented sector.

- Firm funding commitments: Not met. There is no long term plan for the amount of government funding that will be required to deliver the transition to low carbon heat. Government’s funding announcements for energy efficiency and heat are material but will not be sufficient to deliver the upgrades required. Longer term, stable funding is required to deliver the scale of change needed. Government will also need to spend more, use non fiscal measures to drive improvements, or accept a lower level of energy efficiency in buildings than its targets imply.

- Removing barriers to delivery on the ground: Not met. There has not been sufficient action to remove barriers to the installation of low carbon heat and energy efficiency, beyond action to increase funding. Promised action to rebalance the prices of electricity and gas has not yet taken place. This is critical to ensuring that the running costs of a heat pump are lower than those of a gas boiler. Consumer information, financing and logistical barriers such as planning permission remain issues, though government is taking some actions to address these, such as the recent consultation on new permitted development rights for heat pumps.

New infrastructure networks

Overview of key government policy

In line with the Commission’s recommendation, government has set an ambition to store 5Mt of carbon each year through engineered greenhouse gas removals by 2030.

In 2023, the government began development of a business model for engineered greenhouse gas removals, based on a contracts for difference model. The government is also developing a similar business model for bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, which can produce electricity as well as negative emissions.

The government has set an ambition to capture and store 20-30Mt of carbon per year by 2030, and has identified four industrial clusters where carbon capture and storage will initially be deployed. The government has developed business models for transporting and storing carbon, as well as for power and industrial uses of carbon capture. In March 2023, government announced that they would enter negotiations with the first eight projects over support.

No bioenergy with carbon capture and storage projects entered negotiations for support in the first round of projects, though two projects did pass the deliverability assessment. Government has since consulted on potential transitional support arrangements for biomass generators, until they are able to convert. Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage plants are not expected to be operational until at least 2030.

The government has also set an ambition for up to 10GW of low carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030, and is funding this capacity through the Net Zero Hydrogen Fund. The first 11 hydrogen production projects were allocated £2 billion of revenue support in December 2023, with the first projects expected to become operational in 2025.

The government’s transport and storage networks pathway was also published in December 2023, agreeing in principle with the Commission’s strategic case for building a core network. The government has also made progress on design options for hydrogen transport and storage business models, but these are not set to be agreed until 2025.

Assessment of progress

Government is making progress on developing the business models that will underpin the new networks that are needed to meet net zero, and has set out strategies for the carbon capture and hydrogen sectors. A long term plan for the engineered greenhouse gas removals sector is still needed, and the funding position underpinning some of the business models is unclear. More ambition and faster policy development will be required to support these technologies in order to meet the sixth carbon budget and government’s power sector decarbonisation targets.

- Taking long term decisions and demonstrating staying power: Partly met. Government has set out long term targets for engineered removals, hydrogen production and carbon storage and removals. Plans are in place to support the carbon capture and hydrogen sectors, but a detailed plan has not been produced for engineered greenhouse gas removals. Government should also set out a vision for an initial core network to connect producers, users and stores of hydrogen, and emitters and stores of carbon in different parts of the country.

- Policy goals must be matched by effective policies to achieve them: Partly met. Government is making progress on business models to support development of the sector, but these are moving too slowly to give confidence that targets for 2030 and 2035 can be met. Government should also do more to ensure that there is demand for low carbon infrastructure, supporting users in switching away from fossil fuels.

- Firm funding commitments: Partly met. The government has announced up to £20 billion of funding for deployment of carbon capture and storage technologies, but has not announced how this will be allocated. Other business models have not been accompanied by firm funding envelopes, or are accompanied by funding envelopes that are too short term and relatively small. Government should also provide development expenditure support to help projects get to the stage where they can apply for a development consent order. At least £40 million per year will be required to enable the delivery of new hydrogen and carbon pipelines and storage.

- Removing barriers to delivery on the ground: Partly met. These are nascent technologies, so delivery on the ground is limited, but government is beginning to develop an understanding of the practical barriers to deployment and how these might be mitigated, including through commissioning research on planning barriers for hydrogen projects. However, more needs to be done to ensure that hydrogen and carbon capture and storage infrastructure can be deployed in a timely fashion.